Clarity-1: What Worked, and Where We Go Next

On March 14, 2025, Albedo's first satellite, Clarity-1, launched on SpaceX Transporter-13. We took a big swing with our pathfinder. The mission goals:

- Prove sustainable orbit operations in VLEO — an orbital regime long considered too harsh for commercial satellites — by overcoming thick atmospheric drag, dangerous atomic oxygen, and extreme speeds.

- Prove our mid-size, high-performance Precision bus — designed and built in-house in just over two years.

- Capture 10 cm resolution visible imagery and 2-meter thermal infrared imagery, a feat previously achieved only by exquisite, billion dollar government systems.

We proved a ton. We learned a ton.

We achieved the first two goals definitively and validated 98% of the technology required for the third. This was an extraordinarily ambitious first satellite. We designed and built a high-performance bus on time and on budget, integrated a large-aperture telescope, and operated in an environment no commercial company had sustained operations in, funded entirely by private capital.

This is the full story.

VLEO Works

Let's start with the result that matters most: VLEO works. And it works better than even we expected.

For decades, Very Low Earth Orbit was written off as impractical for normal satellite lifetimes. The atmosphere is thicker, creating drag that would deorbit normal satellites in weeks. If the drag didn't kill you, atomic oxygen would erode your solar arrays and surfaces. To succeed in VLEO required a fundamentally different satellite design.

Clarity-1 proved that our design works.

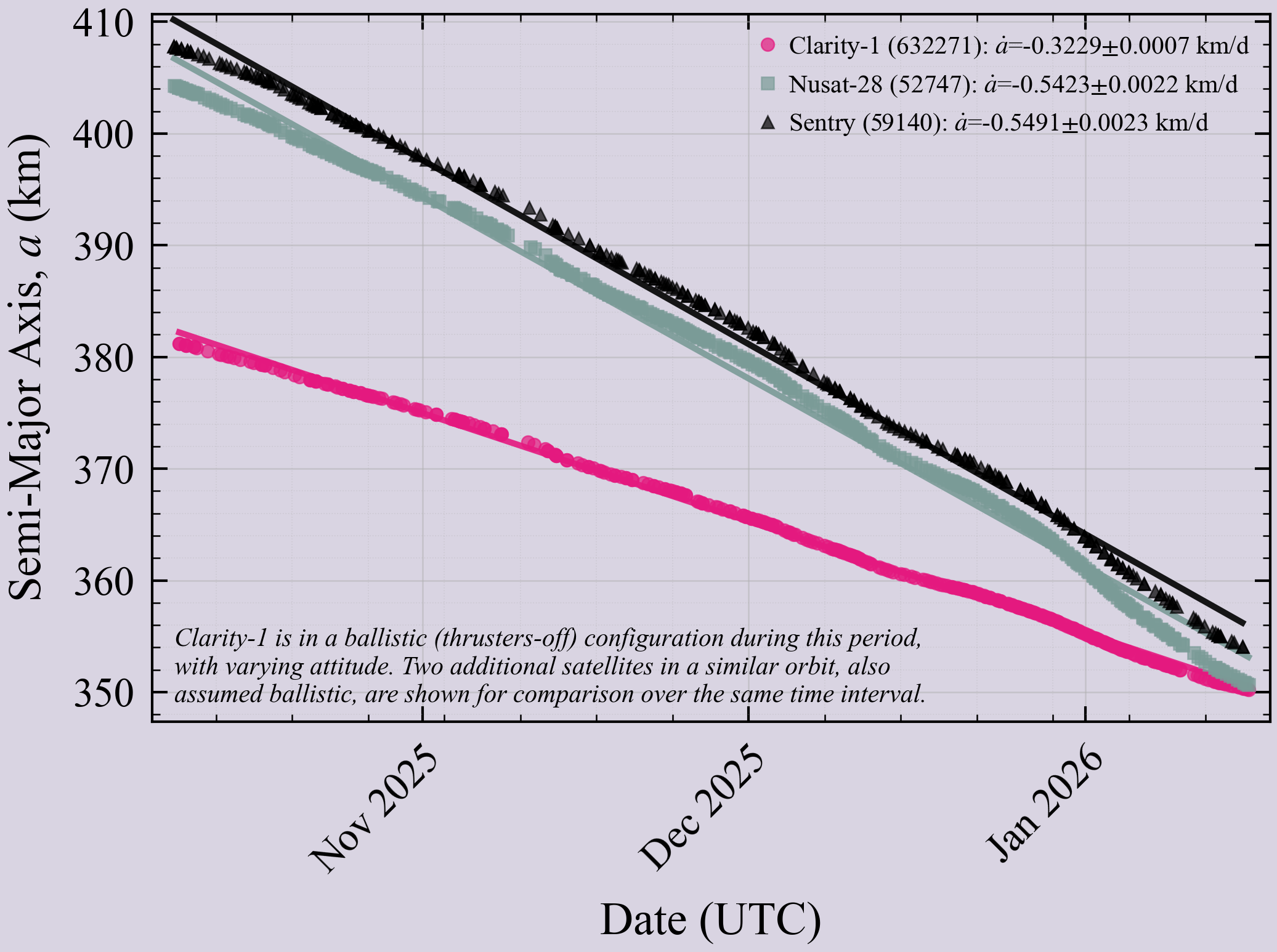

The drag coefficient was the headline: 12% better than our design target. Measured multiple times at altitudes between 350 km - 380 km with a repeatable result, this validates our models producing a satellite lifespan of five years at 275 km altitude, averaged across the solar cycle. This was one of our most critical assumptions, and we exceeded it.

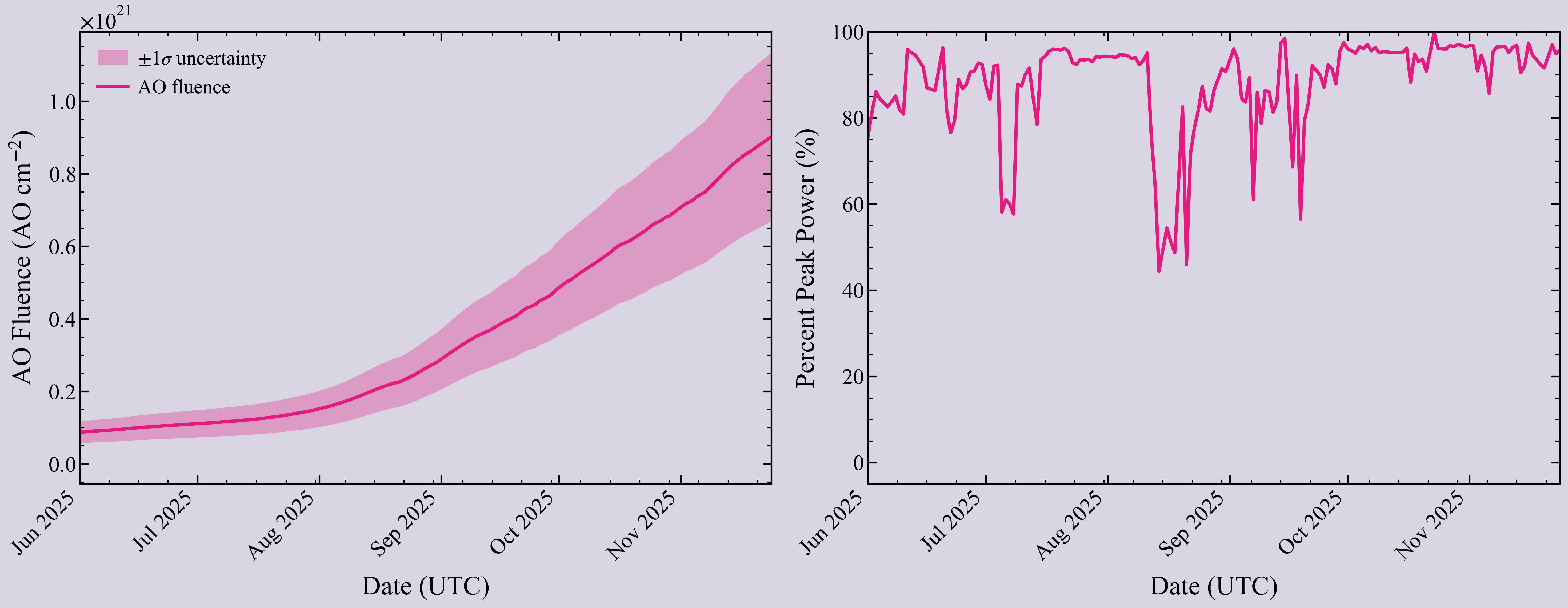

Atomic oxygen (AO) is the silent killer in VLEO. The deeper you go, the more AO you encounter. It degrades solar arrays and other traditional satellite materials. We developed a new class of solar arrays with unique measures designed to mitigate AO degradation. They work. Even as we descended deeper into VLEO and AO fluence increased logarithmically, our power generation stayed constant. The solar arrays are holding up as designed.

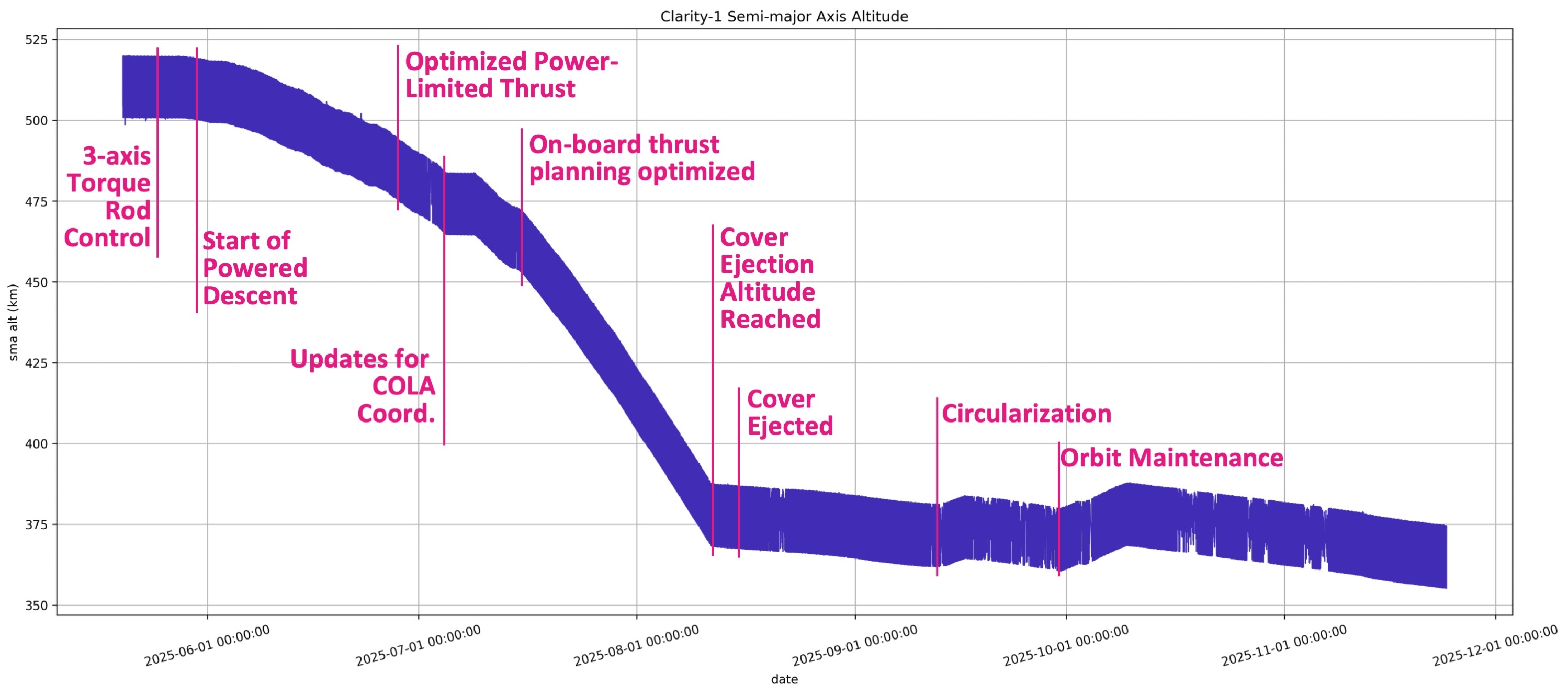

Clarity-1 demonstrated over 100 km of controlled altitude descent, stationkeeping in VLEO, and survived a solar storm that temporarily spiked atmospheric density — the impact on Clarity's descent rate was barely noticeable. Momentum management worked. Fault detection worked. Our thrust planning model was validated against GOCE data (a 2009 VLEO R&D mission) with sub-meter accuracy. Radiation tolerance was excellent, with 4x fewer single-event upsets than expected. Orbit determination was dialed.

We proved sustainable VLEO operations.

The Precision Bus is Flight-Proven

Developed and built in just over two years, our in-house bus Precision is now TRL-9: flight-proven on-orbit.

Every bus subsystem worked. Every piece of in-house technology we developed performed: our CMG steering law, our operational modes, flight and ground software, electronics boards, and our novel thermal management system. We hit our embedded software GNC timing deadlines, we converged our attitude and orbit determination estimators, we saw 4π steradian command and telemetry antenna coverage, and we got on-orbit actuals for our power generation and loads.

Our cloud-native ground system was incredible. Contact planning across 25 ground stations was completely automated. Mission scheduling updated every 15 minutes to incorporate new tasking and the latest satellite state information, smoothly transitioning to updated on-board command loads with visual tracking of each schedule and its status. Automated thrust planning to achieve our desired orbital trajectory supported 30+ maneuvers per day. Our engineers could track and command the satellite from anywhere with internet and a secure VPN.

We pushed 14 successful flight software feature updates on-orbit — and even executed one FPGA update, which is exceptionally rare. The ability to continuously improve throughout Clarity's operational life proved essential — every major solution to challenges we faced involved flight software updates. On-orbit software upgrades are exceedingly tricky to get right, but Clarity-1 was designed from day one around this foundational capability.

Four Weeks of Perfection

The first month of the mission was magic.

An hour after launch, we watched Clarity-1 deploy from the premium caketopper slot into LEO, giving us an incredible view of the Nile River as she separated from the rocket.

First contact came just three hours later at 5:11am MT. Imagine sitting in Mission Control, watching two ground station passes with no data, then on the third: heaps of green, healthy telemetry streaming into all of the subsystem dashboards. Clarity had nailed her autonomous boot-up sequence and rocket separation rate capture. Stuck the landing.

The next milestone — and the one many of us were most anxious about — was our autonomous Protect Mode, basically our VLEO version of Safe Mode.

We estimated a week.

We nailed it 14 hours after launch.

By 6:45pm that same day, Clarity was in Operational mode, ready for commissioning.

"Gotta say it: the last 16 hours have been incredible. I started my shift last night hoping to see one bit of data. I wouldn't have believed it if someone told me we'd be in Protect within 14 hours from launch."— Albedo GNC Engineer

The days that followed were a blur of checkboxes turning green. 4-CMG commissioning complete. Payload power-on and checkout validated. Thermal balance for both visible and thermal sensors confirmed. Our first on-orbit software update went flawlessly.

Clarity uses Control Moment Gyroscopes (CMGs) to steer the satellite, giving us more agility than more commonly used reaction wheels. We moved onto validating GNC modes such as GroundTrack, which we use to point at communication ground terminals.

We moved on to commissioning our X-band radio — the high-rate link to downlink imagery. After we uncovered an issue with our ground station provider’s pointing mode, the 800 Mbps link began pumping down data on every pass. The waveforms were clean. Textbook. A direct representation of how locked in our precision CMG pointing was.

With our first satellite at this level of complexity, we couldn't believe how smoothly it had gone. Years of developing new technologies had been validated in a fraction of the commissioning time we'd anticipated.

Maneuvering over 100 km to VLEO

Next up was maneuvering from our LEO drop-off altitude down to VLEO, where it would be safe to eject the telescope contamination cover and start snapping pictures.

Then came April 14.

One of our four CMGs experienced a temperature spike in the flywheel bearing. Our Fault Detection, Isolation, and Recovery (FDIR) logic caught it immediately, spun it down, and executed automated recovery actions. But it wouldn't spin back up. Manual recovery attempts followed. Also unsuccessful.

Rushing back into CMG operations without understanding the failure mechanism risked killing the mission entirely, so we turned off the other three and put the satellite in two-axis stabilization using the magnetic torque rods.

We had a choice. Hack together novel 3-CMG control algorithms as fast as possible and risk losing another, or figure out how to leverage only the torque rods to achieve 3-axis control with sufficient accuracy to navigate the maneuver to VLEO.

We went with the torque rods.

On satellites this size (~600 kg), magnetic torque rods are typically used for momentum dumping, not attitude control. But we'd built Clarity with unusually beefy torque rods due to the elevated momentum management needs in VLEO. Our GNC team went heads down and developed algorithms to achieve 3-axis attitude control using only torque rods.

Within a month, we had it working.

Both of our electric thrusters commissioned quickly and were working well. But with torque rods only, our attitude control had 15 to 20 degrees of error, sometimes reaching ~45 degrees. And maneuvering to VLEO isn’t “point into the wind and fire” — it’s continuous vector and trajectory management across an orbit. That kind of control error meant inefficient burns and a much harder descent plan.

As the descent progressed, however, the team learned and iterated. With more iteration and flight software updates, we uploaded onboard logic informed by several sources of live data that dialed in our thrust vector control to within 5 degrees of the target. The autonomous thrust planning system we built enabled us to claw back performance that nearly matched our originally projected descent speed.

We maneuvered safely past the ISS and entered VLEO. Eager to pop off the contamination cover.

Lens Cap Jettison

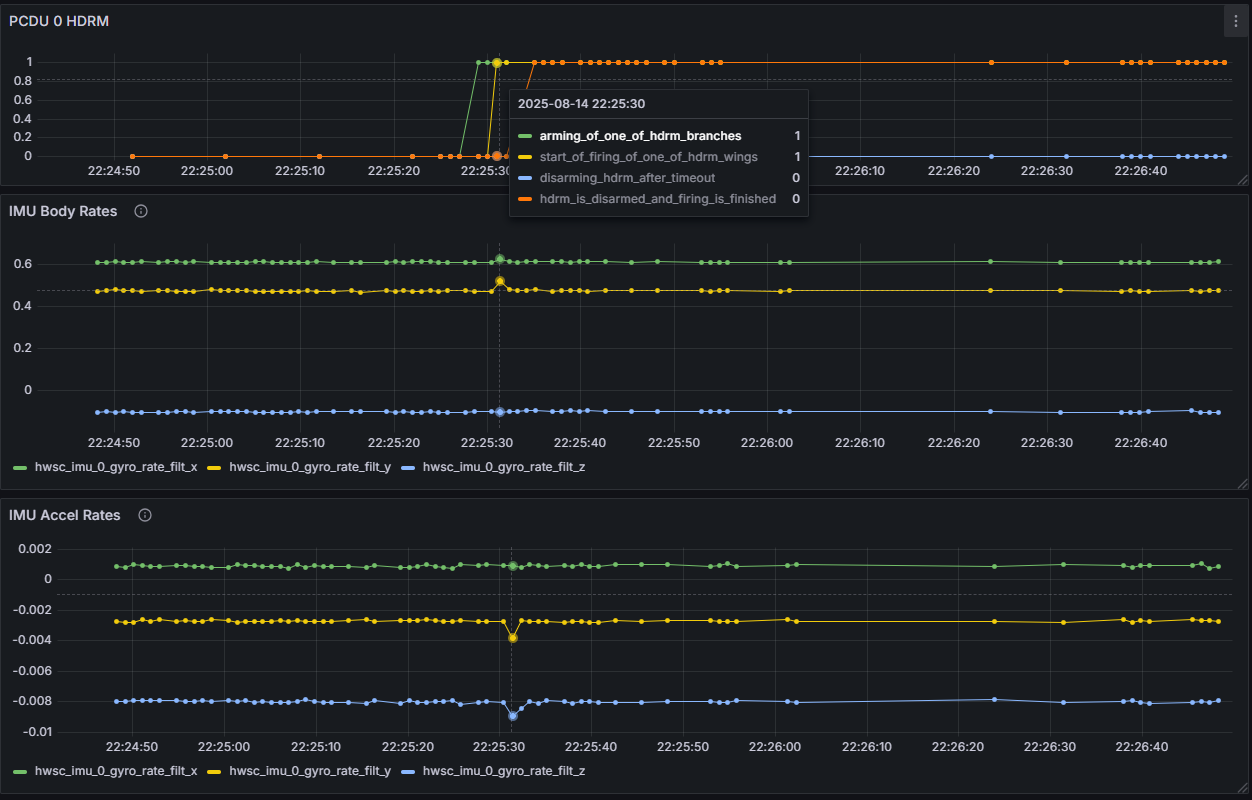

Once we reached safe altitude, it was time to jettison the contamination cover protecting our telescope.

There are horror stories about contamination covers getting stuck after months of temperature fluctuations.

Clarity's was flawless. I'll never forget seeing this blip in telemetry live — confirming through Newton's third law that the jettison was successful. Shortly after, LeoLabs confirmed tracking of two separate objects.

We were ready to start imaging.

The Imaging Journey

Here's where it got complicated.

Our GNC and FSW teams were close but not yet finished with the new 3-CMG control law. CMGs are rarely used in commercial space, let alone by a startup. Then take one more step: singularity-prone 3-CMG control that to our knowledge has not been attempted on a non-exquisite satellite, and certainly not developed and uploaded on-orbit. Traditional algorithms require at least four CMGs to provide capability volumes free of singularities.

We were eager to make some amount of progress, so we started imaging on torque rods even though there would be severe limitations: 50+ pixels of smear, large mispointing from the wobble of torque rod control due to earth's magnetic field, and downlink limited to at best two small images per day. The last two constraints meant we were at risk of spending precious downlink capacity on clouds.

Sure enough, the first two days of pixels were mostly clouds, but we were happy to peek through a little in this image.

Although we couldn't control attitude accurately, we did still have good attitude knowledge after the fact. AyJay whipped up a clever idea with Claude Code that automated posting weather conditions in Slack for each collection. We analyzed that to determine which images were likely clear, and selected those for downlink.

Boom:

.jpg)

We adjusted the focus position a few times, and images continued getting better.

Then, 3-CMG control was ready.

Out of the box, the new algorithms and software performed perfectly.

This visualization shows real telemetry of Clarity performing seven back-to-back imaging maneuvers, with limited 3-CMG agility, followed by an X-band downlink over Iceland minutes later. The satellite was executing sophisticated attitude profiles with very low control error. Fiber-optic gyro measurements showed exquisite jitter performance.

In real time, collecting and downlinking those seven images took ten minutes.

And this is where our ground software really showed its teeth. On most missions, “data on the ground” is just the start — turning raw bits into something viewable is a slow chain of handoffs and batch processing. For us, within seconds of the downlink finishing, the image product pipeline was already posting processed snippets into our company Slack. Literally seconds.

That end-to-end loop — photons in orbit to a viewable product on the ground, within minutes — is a capability that’s still rare in this industry.

As expected with smear reduced, image quality improved immediately.

%20copy.jpg)

We were ready to execute focus calibration.

Large telescope optics experience hygroscopic dryout during the first few months on-orbit — moisture trapped in materials during ground assembly slowly releases in the vacuum of space, causing the focus position to drift. Dialing in best focus requires dozens of iterations: capture images, analyze sharpness, adjust focus position, repeat. Each cycle gets you closer to the optical performance the system was designed for, and our telescope’s on-ground alignment was verified to spec.

We continued to iterate.

.jpg)

After a few iterations of this, we could start to see cars.

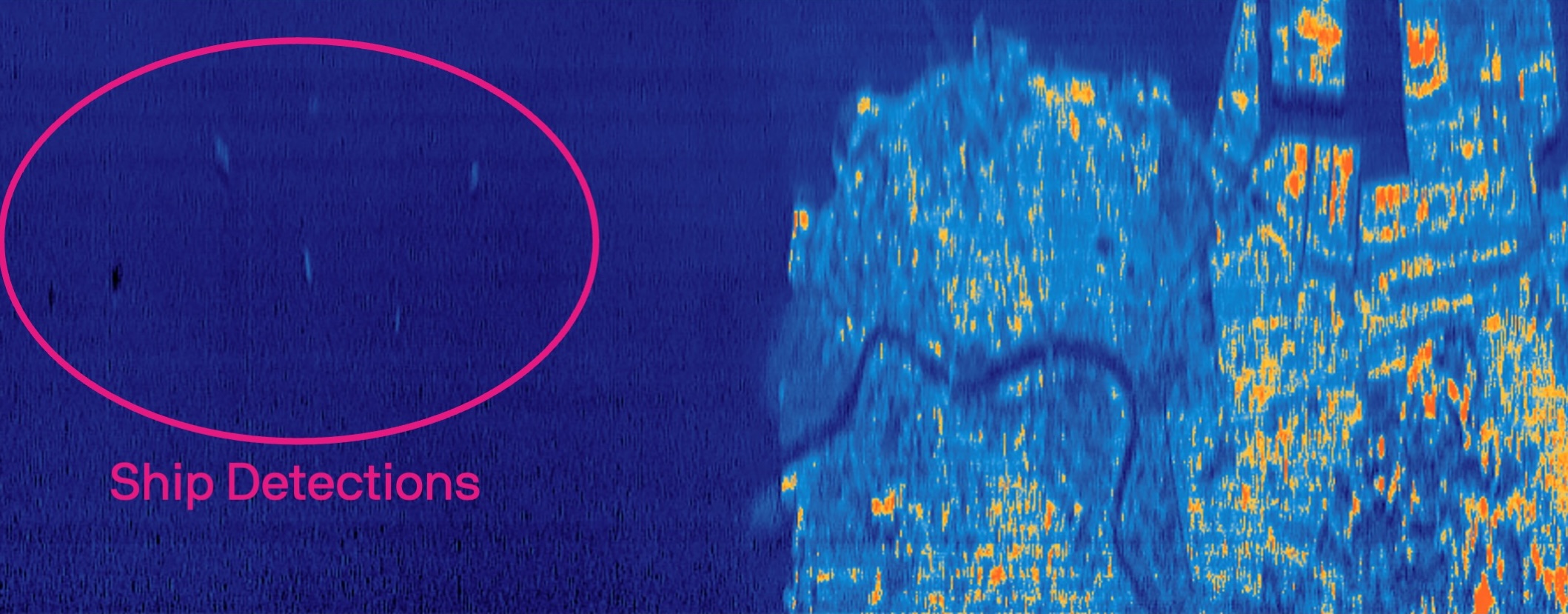

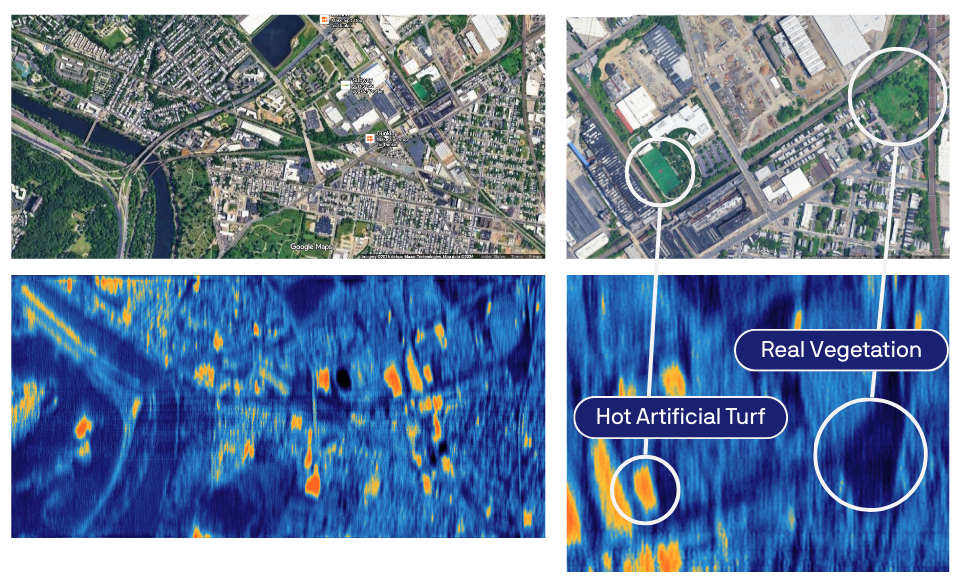

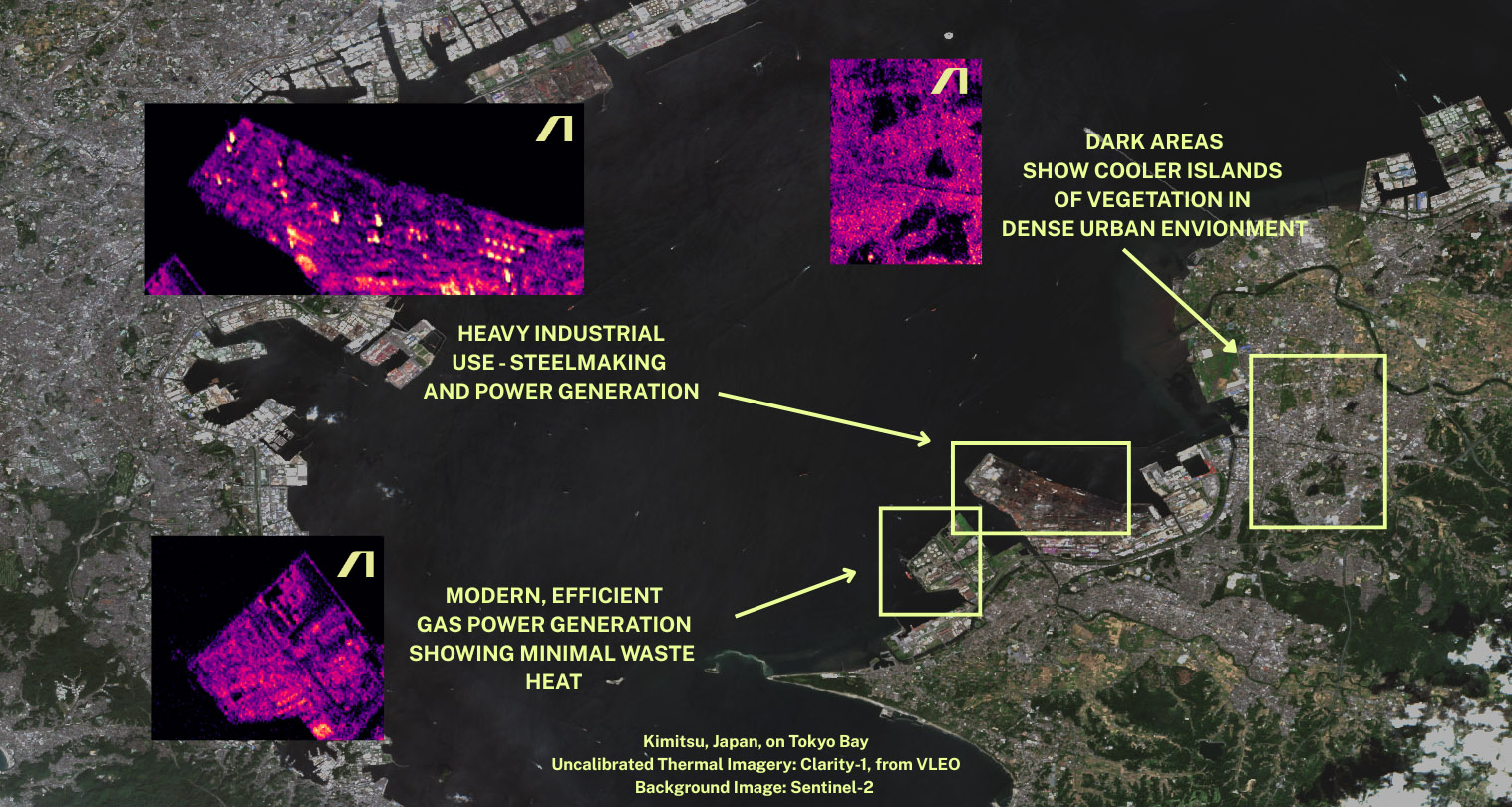

Even this early into imaging, the infrared images blew us away. Using a low-cost microbolometer — a fraction of the price of cooled IR sensors — we captured thermal signatures that showed ships in Tokyo Bay, steel processing facilities where we could distinguish individual coke ovens from their smokestacks, and distinct signatures between real vegetation and turf — a good proxy for camouflage detection. Day or night, clear as day.

Three days into the excitement, CMG problems started again.

A second CMG began showing the same telemetry signatures we now recognized as warning signs.

What we had learned from the investigation: the allowable temperature specifications of the CMGs were much higher than the true limit, constrained by what the lubricant inside the flywheel could handle. A straightforward fix for the future — an unfortunate corner case to learn about in hindsight.

The second CMG showing issues was also on the hot side of the satellite. While we had overhauled the vehicle and CMG operations to prevent additional bearing wear, the damage had already been done in the first month of the mission.

We spent months trying everything we could to get the CMGs to operate sustainably. The team attempted many clever solutions, one of which revived the first CMG that had locked up. We uploaded a feature to select any 3 of the 4 CMGs for operator commanding. But we weren't able to get sustained, reliable operation.

Despite the CMG challenges, here's what the imaging journey proved.

The full end-to-end image chain works. Photons hit our optics, get captured by our sensor, processed through payload electronics, packetized and encrypted, transmitted via our X-band radio, received on the ground, and processed into image products. The entire chain is validated.

The end-to-end loop is fast. Within 30 seconds of a downlink, processed image snippets were already posting to our company Slack.

Sensor performance exceeded expectations. Dynamic range, radiometry, color balance, band-to-band alignment — all look great, even on uncalibrated imagery.

We can scan out long images. Our line-scanning approach produced strips 20-30 kilometers long, exactly as designed.

Pointing accuracy and high quality telemetry validates the ingredients for precise geolocation. The data we need to pinpoint where each pixel lands on Earth to <5m (closed-loop CE90) is there.

Jitter and smear are low. Fiber-optic gyro measurements confirmed 3x lower smear and 11x lower jitter compared to our goal — a critical ingredient for exquisite imagery.

Our proprietary image scheduler works. The automated system that plans collections, manages constraints, and optimizes what we capture each day performed as designed.

Where Clarity Is Now

Nine months into the mission, we lost contact with Clarity-1.

By that point, we had largely exhausted our options on the CMGs. The path to further image quality improvement had effectively closed.

We had been tracking intermittent memory issues in our TT&C radio throughout the mission, working around them as they appeared. Our best theory is that one of these issues escalated in a way that corrupted onboard memory and is preventing reboots. We've tried several recovery approaches. So far, none have worked, and the likelihood of recovery looks low at this point.

But here's what matters: the VLEO validation data we collected is sufficient.

We combined a state-of-the-art atmospheric density model, our high-fidelity orbital dynamics force models, and months of natural orbit decay data from 350 to 380 km altitude to determine Clarity’s coefficient of drag — with repeatable results at different altitudes. That drag coefficient, paired with our demonstrated ability to maintain altitude in VLEO for months using high-efficiency thrusters, tells us exactly how the vehicle behaves under aerodynamic drag across the VLEO regime — and validates an average five-year lifespan at 275 km across the solar cycle. Telemetry from our solar arrays, together with onboard atomic oxygen sensor data, shows peak power generation stayed constant after exposure to VLEO levels of AO fluence — proving our AO mitigation worked.

Thanks to our friends at LeoLabs, we've validated that Clarity is maintaining attitude autonomously. She's still up there, still oriented, still descending through VLEO. Just not talking to us.

Even before this, we had started developing an in-house TT&C radio for our systems moving forward, rather than reusing this radio that was procured from a third party. We’ll incorporate learnings from this reliability issue into that.

We're still working the problem. This chapter isn't over yet. But even if it is, Clarity-1 gave us what we needed to build what comes next.

98% of The 10 cm Imagery Pyramid

If you think about exquisite imagery as a pyramid, we needed 100% of the systems working together to achieve the pinnacle: 10 cm visible imagery. We got to about 98%. Everything else in that pyramid — the entire foundation — is proven and retired.

Our drag coefficient. Our atomic oxygen resilience. Our solar arrays. Our thermal management. Our flight software. Our ground software. Our CMG steering laws. Our precision pointing algorithms. Our payload electronics. Our sensor performance. Our image processing chain. Our ability to operate sustainably in VLEO. Our team.

All validated.

We know exactly what to fix. It’s straight forward: operate the CMGs at lower temperature. The system thermal design is already updated in the next build to maximize CMG life going forward.

Beyond the CMGs, there were a handful of learnings on the margins. We learned our secondary mirror structure could be stiffer — already in the updated design. We learned we could use more heater capacity in some payload zones — already fixed.

We learned from the things that worked, too. We're well down the development path for next-gen flight software, avionics, and power distribution. Orbit determination and geolocation will be even better. Additional surface treatments will improve drag coefficient further. Power-generation will increase while maintaining the proven atomic oxygen resilience. The list goes on.

The path to exquisite imagery is clear. And that’s only one of many exciting capabilities unlocked by sustainable operations in VLEO.

What’s Next

Our next VLEO mission will incorporate these learnings and demonstrate new features that enable missions beyond imaging — we’ll share more details soon. In parallel, imaging remains a core focus: we’re continuing to build optical payloads for EO/IR missions as part of a broader VLEO roadmap.

The successes of Clarity-1 reinforced our core conviction: VLEO isn’t just a better orbit for imaging — it’s the next productive orbital layer.

The physics are unforgiving, but that’s exactly why it matters. Go lower and you unlock a step-change in performance: sharper sensing, faster links, lower latency, and a new level of responsiveness. The reason VLEO has been written off for decades isn’t lack of upside — it’s that most satellites simply can’t survive there long enough to matter.

Now we know they can.

Clarity proved the hard parts: sustainable VLEO operations, validated drag and lifetime models, atomic oxygen resilience, and a flight-proven high-performance bus. We’re not speculating about VLEO. We’re operating in it, learning in it, and capitalized to scale it.

Onward,

Topher & Team Albedo